How do you [solve a problem like] AI?

Thoughts on making it fit and bringing it ‘round.

This week everyone in my department received an email solicitation to learn more about a product called Rumi, one that purportedly can “capture and analyze how a student's writing evolves across drafts to detect improper AI use”. The email -- authored by a former instructor who assures readers that they know just how problematic plagiarism is with tools like generative AI at hand – invites a click to peruse the advert about what the software has to offer.

This is not a pro-AI detection post. Rather, it’s quite the opposite. While I did click because I am always curious, I have no intention of seeking out a demo nor of using this or any other ineffectual AI-detection product. My husband and I (hubs being, btw, author of the “coming soon” newsletter titled Higher Education AI) talk about AI issues like this all the time and when I mentioned the recent email barrage noted above he suggested that I write a bit about the issue here on Substack and I took him up on that challenge! So we have him to thank for this post ;).

The problem of AI in our classrooms is something all instructors need to think about, but I do not take the side of seeking AI-use with the possible charge of plagiarism in the back [or forefront] of my mind. Rather, as you might surmise from my leading meme, I see the solution space in a much more creative light.

Establishing the problem space

Rogers and Hammerstein make clear in the lyrics to Maria from the Sound of Music that the problem Maria poses to the convent is not one best addressed with punishment. If you are a Sound of Music aficionado you know the story already. The song features Maria’s personal qualities and how these don’t fit convent life, suggesting instead that Maria is suited something else entirely.

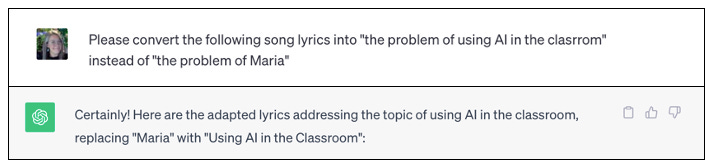

With my family looking over my shoulder as I started playing around with the AI-teaching and “problem with Maria” comparison, my husband suggested that I ask ChatGPT to revise the lyrics of Maria, replacing the protagonist with “using AI in the classroom”. I took him up on that challenge too, and to great effect.

Here’s a sample of the resulting revision – it is on point! (note: you can find the full text response here, complete with my non-expert prompt engineering false start, haha).

I'd like to say a word in its behalf

Using AI makes me laugh

How do you solve a problem like using AI in the classroom?

How do you make it fit and bring it 'round? [ “catch a cloud and pin it down” – clever revision!]

How do you find a way to teach with using AI?

A digital wizard!

A data-driven choice!

A trend!

So how do we “make it fit and bring it ‘round? If you’ve played with ChatGPT at all, the next lyric snapshot should resonate too:

Many a thing you know you'd like to tell it

Many a function it ought to understand

But how do you make it stay

And listen to all you say

How do you keep its algorithms well in hand

Oh, how do you solve a problem like using AI in the classroom?

How do you hold a data stream in your hand?

When it's with you, you're confused

Out of code and bemused

And you never know exactly where you stand

Unpredictable as software

It's as dynamic as a dare

It's a marvel!

It's a puzzle!

It's a plan!

These lyrics creatively capture the promise and the peril of using generative AI in educational contexts.

It’s Promise: On the surface it does seem rather marvelous!

Instant answers at our fingertips? Yes, please!

Near instant essay composition? Sign me up!

References in APA Style? Be still my beating heart.

Generate accurate Python Code? Life saver!

Summarize lengthy text in the blink of an eye? Sigh. Imagine the time savings.

It’s Peril: But of course, there is no free lunch, even with ChatGPT. Generative AI products are moving targets, where their host companies are continuously working to update and refine the programming. Just when we think we understand what the programs can and can’t do, they change.

For example, as the world became aware of ChatGPT late in 2022 and early in 2023, it became clear that the program could not do math (in hindsight, duh, it’s a large language model [LLM], not a large numeracy model), but skip ahead to the present and OpenAI has a workaround for paid customers using GPT4, where you can select a data analysis feature to process mathematical prompts.

As well, ChatGPT hallucinates, in that it makes plausible sounding responses though elements of that response may be false, as in unfounded, when compared to the real world. Anything from content to source references may be hallucinatory. While OpenAI is reputedly working on this issue, it remains an intractable one. So using ChatGPT to generate non-fiction content is a dicey endeavor. All the program does is predict what the most likely linguistic responses should be – it does not have a reality-check feature.

However, there is no ignoring the fact that LLM responses can be alarmingly coherent. As I type this newsletter I am remembering the February 2023 buzz around NYTs journalist Kevin Roose’s conversation with Bing Chat, wherein the program stated that it wanted to be alive and invited Mr. Roose to leave his wife. The natural-language-processing ease of that exchange was indeed eye-brow-raising. But it was still just an exercise in prediction. LLMs remain “narrow AI”. They do one thing and one thing only: predict text based on common usage patterns. The prediction is uncanny, but it is still just that. As of October 2023, General AI does not [yet] exist. These programs have GPUs (graphical processing units) not CNSs (central nervous systems).

In need of an AI Primer? Check out the WIRED Guide to AI for a brief history of AI, glossary (or rather, in their words “a decoder ring”) of terms, and discussion of the issues I raise here and more.

Seeking Solutions

Generative AI creates compelling content – no doubt about that. So what do we do about this, as educators? We have two options.

We can go the “ban and policing route” where detection of AI use and the possible charge of plagiarism carries. I see this route as a no-go for several reasons. For one, as of this writing, the false positive AND false negative rates generated by detection programs are too high for comfort. If one is going to seek out plagiarism and make charges against a students’ academic integrity, one needs foolproof evidence and AI detection programs cannot offer us that. For another, LLMs are carriers for all the bias that’s contained in human natural language usage. The programs were trained with actual human language use, after all. Any bias in the training set comes out in the product and its functionality. LLMs act as mirrors in this regard. Bias in – Bias out. The detection programs perpetuate human biases too. They are more likely to flag non-native English writer’s text as AI-generated (see discussion of this issue here), for example.

All this points to the need for an alternative approach. Educators can instead view AI-LLMs and the like as tools to support ours and our students’ writing endeavors. Writing support tools are not new to the ed-tech landscape. Heck, Google has been suggesting text completion (i.e., “smart compose”) since 2018. AI infiltration has been on a slow-creep working it’s way into our lives for quite some time. And we educators have no say about the fact that such creep will continue.

We can’t stop the creep, and really I don’t want to. Embracing technological advances in all their disruptive glory and doing the mental work needed to try and make good on the Promises of AI in education is the only viable way to go. Emphasis does indeed belong on “disruptive glory” though. Generative AI has made educators’ jobs harder – we now have to learn more and change our ways to help our students learn more, too. Sigh.

Back to that list of promises I noted above. Our challenge is to note the program’s capabilities and guide students’ use in a developmental fashion.

How do we take these promises and turn them into teachable moments?

Instant answers at our fingertips? Yes, please! ←- teach about hallucination and how to use ChatGPT to start but not finish an assignment.

Near instant essay composition? Sign me up!←- use as a tool to brainstorm composition seeds, then build on those seeds with students’ own ideas

References in APA Style? Be still my beating heart. ←- cross check any references in databases, to make sure they are real. Use this an a ways of teaching students about databases and how they differ from web search engines.

Generate accurate Python Code? Life saver! ←- like with refs, use the generation feature as a way of self-checking students work as they learn the coding language

Summarize lengthy text in the blink of an eye? Sigh. Imagine the time savings! ←- compare AI generated “abstraction” to human generated abstraction as a way of teaching the difficult skill of synthesis

The 21st century is happening now, and we need to help students prepare for the party.

Outside of classrooms, the world is similarly experiencing disruption too, but many are already embracing generative AI in their work and figuring out "fair use" policies. Last winter the Atlantic Monthly published an essay about AI titled "The most important job skill of this century: Your work future could depend on how well you talk to AI". That is, AI is embedded in the workplace, thus banning AI from educational spaces -- or even just castigating its use – is counterproductive to the broader aims of education. If our aims with education are to prepare today’s youth for a productive adult life, we need to help them learn how to live with and wisely use AI. We need to call for “AI-literacy for All”.

I am not alone in making such a call for AI Literacy for all, and for embracing rather than vilifying AI in educational spaces. Yesterday Stefan Bauschard posted to his substack newsletter a healthy round-up of voices all advocating against policing and for teaching appropriate use instead (see here, too, for more on Bauschard’s position on AI Literacy, as well).

In more formal venues (i.e., academic journals rather than Substack newsletters), I am keeping an eye on an exciting and growing literature on what K-12 AI-literacy curricula should entail. Continuing education work to bring teachers up to speed on AI to help them embrace wise AI use practices in their teaching is also happening, it just takes work to find that work (if you are Facebook, there’s an excellent group called Higher Ed discussions of AI writing that has quickly become a very rich source of information and ideas). And it takes effort to adjust our mental sets and practices around this work.

But it’s worth it. Change has always been a constant in development and in education.

Coming back around to ChatGPT’s revised Maria lyrics: “holding a data stream in your hand” is an impossibility. Rather than think about AI in static terms as something to master, we must remember that it’s “dynamic as a dare” (I love that turn of phrase!) and think about how to approach it in similarly dynamic terms. Some of us in the profession need to learn about the fundamentals, and all of us need to revise our approaches to appropriate tool use. Educators need time to adjust their frames of reference and attitudes towards technology in learning spaces. This is hard work.

Technological advances are always disruptive. Back in 2008 Nicholas Carr published a piece for the Atlantic Monthly titled Is Google Making us Stupid (a precursor to his later published book titled The Shallows) where he takes readers on a historical journey of professionals bemoaning the ruinous nature of technology. With each new iteration – from printing presses to LLMs – comes a cycle of stress and recovery and forward motion. We are in one of those moments now. As we work through the stressors of technological disruption, we can emerge from it better for it.

Just as Maria faced much hardship as she struggled to find a life for herself outside of the convent, we too can climb the necessary mountains to seek a brighter day on the other side (note: I didn’t ask ChatGPT to rewrite this song – rather I borrowed shamelessly from Rogers & Hammerstein’s original) as we level up our teaching game. Will some students slip through the cracks and cheat the system with generative AI without giving appropriate credit to their sources? Yes. Some students will always cheat. But with wise use policies and positive, creative AI-inclusive practices as the norm, more students will find that AI can be a like that “rainbow path” or “ford to the stream” that Rogers and Hammerstein waxed poetic about when they wrote the music so long ago that still resonates today.