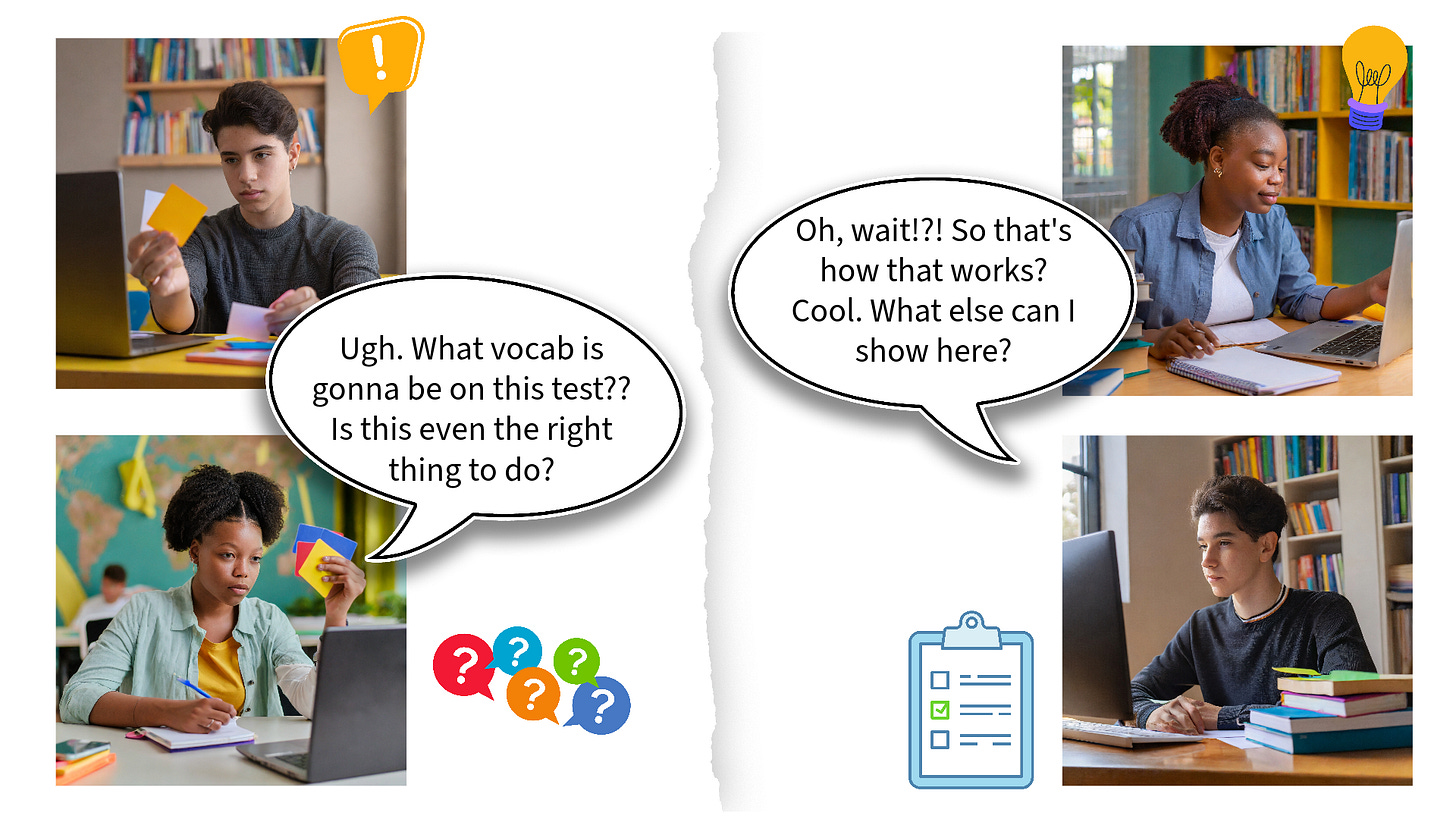

Remember that panicked two-week period of frantic pivoting from face-to-face to zoom-school, way back in the spring of 2020 (omg, was that only just three years ago?)? At the time it felt like this …

… like I was doing more knee-jerk reacting than anything else. I vividly remember the moment when I first came across the meme I feature above and the relatable laugh-cry sesh that ensued. At that time, I ran a paper-n-pencil classroom. Whenever we did active learning in a class period, students wrote responses down on notecards that they turned in at the end of class. While I did require that formal writing assignments be typed, tests were completed by hand, in the classroom, in a traditional closed-book style. Students studied, many crammed, and we moved on.

All that is to say: I had a steep learning curve when I had to change my ways on a dime to become fully digital, that is, paperless. I had a lot of decisions to make, and had to make them fast.

Given that we weren’t going anywhere and I actually had more time than usual to implement changes, I made up my mind to consider how my decisions lined up against equity and inclusion friendly practices. I knew that many of my students were heading home to a situation that would not be conducive to traditional class engagement and test prep. I also knew quite a bit about learning science principles that point to effective long-lasting learning. So I gathered more info on EDI (i.e., equity, diversity, and inclusion) and UDL (i.e., universal design for learning), and got busy. And then I made some big changes. The time I took then to really think things through paid off. Three years later, I am happy to report that many of the changes I implemented ended up improving my teaching, which also improved student learning, too.

Wow, right?

Every so often I jump into conversations on the Society for Teaching of Psychology Facebook group, and one of those conversations is what inspired me to write this newsletter. Thanks to you all, you who asked me to elaborate on my “Mastery Testing” approach. That is, in today’s “Trade Tools” newsletter I want to discuss why and how I changed my testing approach and why I maintain it now, so many years post-zoom-school.

What is Mastery Testing?

When it comes to assessing students’ learning, there are two approaches you can take. One is a summative “snapshot” approach and the other is to take a mastery “revision” approach.

[Note: definitions above are my own “take”]

The summative approach is the common one; it’s how I experienced assessment K-12 and beyond (even in some grad school classes). The Mastery approach isn’t new, but it is not as commonly used, though since Covid and with a rise in attention paid to EDI and UDL this is changing.

Why is change so slow to take hold? Change is hard, and we are not often reinforced to do so. And the typical rational for sticking with the traditional summative approach, captured in the following three soundbites, is compelling:

The work of memorization is what “gets the content in your head”

When everyone has the same amount of time to prepare and to demonstrate their knowledge, it’s the most fair

Cheating is minimized when you can have your eyeballs on the students while they take the test

Following, concerns about mastery testing tend to go something like this:

If students aren’t memorizing, are they actually learning?

Is it fair that some students take the test more times than others?

You can’t control cheating if students take the test on their own. How do you know it’s their own work?

I knew about Mastery testing before covid, and admit that some of the soundbites above did cross my mind. While I knew that there was merit to the mastery ideal, I had not given myself permission to really think through how to approach it. That is, until the pandemic forced my hand in this. As I prepared for distance teaching, my thoughts on “what’s fair” seismically shifted.

For example, I reminded myself that:

Memorization tactics like flashcards on quizlet are not actually the only way to get content into learner’s heads. Memorization tactics like cramming are exactly the opposite of what we want students to do as they progress through our major.

It turns out that everyone does not have the same amount of time to prepare for summative tests. Some (most!) students work while in college. Some students are also parents. Some students care for their parents, or younger siblings, or extended family members. Some students shoulder multiple responsibilities in addition to their own learning. From this point of view, it’s summative testing that is not at all fair because in reality everyone doesn’t actually have equal time to prepare.

Cheating happens no matter what we (faculty) do. It turns out that there isn’t much we can do about this, as faculty. Our decisions may exacerbate or relieve pressures that lead students to cheat, but usually the act of cheating is not caused by “us” – the professors. Rather, life conditions can be complicated for many students and many forces come together in times of stress making cheating more or less likely. As well, there will always be some students who get a thrill out of trying to game a system, and that has nothing to do with us and our decision making. They will seek that thrill and push boundaries no matter what kind of testing format we use. Cheating, again, isn’t really about “us”.

Following these realizations, in spring 2020 I decided that mastery testing was the only reasonable way to go. The formula I came up with reflects my thoughts on how to combine Learning Science with EDI principles. I didn’t use a single source to guide my approach. Rather, I came up with an approach that made sense to me, given my knowledge of Learning Science and EDI principles. That is, I made it up, but with educated decision making. I was winging, yes, but winging it with substance, you might say.

Prf. K.’s Mastery Testing Approach.

Here’s what I came up with then, and am still doing, today.

Timing. Students get 24 hours to take the exam. This is a reasonable amount of time where students can fit multiple “takes” into their busy schedules. The test doesn’t take 24 hours to complete, rather, they have 24 hours to demonstrate mastery. I find, and believe there’s literature to support this though I don’t have a citation on hand right now, that there’s a diminishing return to much more time than this. Forty-eight hours, for example, lets procrastination tendencies seep in and students end up cramming again.

Content. To make the tests work as intended, the test content cannot be “discoverable” online. That means I do not use text-book test bank questions, nor do I reuse the exact same exam each time. I make sure that content is balanced to reflect what students have read and what we have covered in class. Content that was in the readings but was not covered in class is fair game, and content that was in both class and the readings is a sure-bet in terms of what I include. While I create each test anew each semester (i.e., I teach 5 different classes a year, but don’t “test” in all classes, so it’s not as intensive as it might seem at first glance), I do re-use some content, but I always revise more than I copy.

Testing format: Multiple Choice. To put the testing effect to work for students, the bulk of the test is multiple choice; tests range from 30 – 60 questions depending on the class. I set up the test in the LMS (we use Moodle where I teach) such that after each pass through, students are told which questions they got wrong. The LMS randomizes the answer options, so on the next pass through, the answer options show up in a different order. I do not label the options “a,b,c,d” rather I just let the LMS display a radio button by each answer option. I can randomize the question order too, though I don’t always because sometimes I refer to previous questions. Each time a student takes the test, they take the whole test. That is, they can’t just make corrections.

In this way, the testing effect is put to use for students, as are other learning science principles. In more traditional multiple-choice testing, the standard practice is to present students with a balance of definitional (i.e., easy) questions and applied or evaluative (i.e., hard) questions. The more evaluative qs, the harder the test. In my mastery approach, I want to challenge students to think and work for the answers, so the balance of questions are applied and evaluative. As such, students have to actively engage with their materials, synthesizing and applying content from multiple sources as they go through the exam.

It's not all that uncommon for students “new” to this approach of testing to think, at first, that they don’t have to study (Open book?? Yahoo! Bring on the free time!!). In fact, some first-year students who are fresh out of high school will sometimes not even take notes in class at first, despite my recommendations. After that first test though, they realize that a mastery test isn’t a cake-walk, and they change their behavior. It turns out that the best way to prepare for a mastery exam like mine is to take notes in class, and then to revise notes to integrate that content with class readings. Students don’t need to make flashcards, rather they need to think about the meaning of what they are learning, and how to compare/contrast/apply/evaluate that content – all the things we want students to be able to do, but that flash-cards disallow (flash-cards being students go-to, when their experiences with testing are all about memorization). Students who enter into the test having worked conceptually or evaluatively with the content, find that they only need to take it a couple of times to show mastery. Some students end up taking the test 4 or 5 times too, though. That is, as long as students have notes and resources, the evaluative studying can happen either before the exam or during the exam.

On that STP-Facebook group discussion about mastery testing that prompted me to write this newsletter, a handful of folks asked me if I would share an example of my test-items. I hesitate to do that for a couple of reasons:

I don’t want my test questions to leak out into the internet.

The relative difficulty of a question is, well, relative. That is, it’s relative to the level of the class (i.e., students’ background knowledge), the readings students engaged with, the in-class experiences they’ve had, and so on. So instead, I would remind folks that in general: definitional questions are easy, and evaluative questions are hard. But if definitional questions focus on obscure content, that could make them feel hard, and if evaluation type discussion happened in class and students all have that evaluation content in their notes, that could make an evaluative question feel “easy”.

Testing format: Essay. Given than I want my testing format to encourage students to engage with the to-be-learned content in deeper ways than usual memorization techniques allow, I include some short answer/essay questions in my tests too. I do not give students multiple chances on these responses, though they too are open-book / open note, and students have the same 24-hour time period to complete the whole test.

How does mastery testing play out?

Students’ remarks about this approach to testing initially surprised and delighted me! After the first test in Spring 2020, a student told me that the test made him want to work harder because he could see that he had a fair chance of showing me what he had learned. I receive remarks like this all the time.

As well, students tell me that they can’t really cheat, because they can’t find the questions in any of the usual go-to sources (I understand that most test-banks are discoverable if students know where to look, and most do, I expect).

I only have experience using one LMS with this, and Moodle shows me a few things that I find really informative about student testing behavior. For example, on the multiple choice portion of the test, I see:

How many times each student took the test

The time stamp for starting and completing each test attempt

The amount of time spent on each test attempt

These simple metrics tell me what I think is “enough” about student integrity. When I see a student complete the entire exam in less than 15-30 minutes (time flag depends on how long the test is) and earns a respectable score, I expect something is up. When that happens I will invite the student to discuss with me what their approach was and how it came to be that they were able to demonstrate mastery in such an unusually rapid manner. In three years time, this has happened exactly 3 times.

On the essay / short answer portion of the test, what do I see? I can tell when students cut-and-paste content from other sources because it’s hard (or maybe they don’t know how?) to adjust formatting. So that’s easy. Sometimes I wonder about wording that was clearly typed in (i.e., nearly all of my students turn in weekly reflections so I have a sense of their written voice before exams) but also different from what I would expect, and in those cases all I have to do is “copy and then paste” a response into a browser to look for a hit. When this happens, I do the same: I invite the student to tell me why they decided to not follow the instructions about paraphrasing and citing sources, and where it goes from there depends on their individual responses. This happens a little more frequently than students who manage to get a classmate to share answers with them, but in all, it doesn’t happen all that frequently at all.

The greatest outcome I’ve seen, by far, is evidence of lasting learning. I teach at a small liberal arts college where I see students in multiple classes. Over the span of the last three years since I’ve implemented mastery testing, students show me “knowledge transfer” quite frequently. I found this astonishing at first, considering that my first cohort of students doing mastery testing were students who experienced the most intense covid-disruptions. While the “tenor” of water-cooler talk amongst faculty was that that those three semesters most affected by the quarantine were write-offs, I found quite the opposite. Students who had learned with me on zoom, a year, or even two years later, were able to spontaneously connect what they had learned “then,” to the current content they were learning “now”.

While I know that this is anecdotal evidence rather than an empirically gathered assessment of data, the frequency and consistency of students’ transfer is notable, if not down right astounding. Back in my old “summative assessment days”, students rarely remarked that they thought my tests were unfair, but they did cram for them and would often sheepishly remark in the next class that they’d forgotten much of what they had studied in prior classes. As well, I frequently had hopes for thoughtful essays dashed, as students - pressed for time and feeling hot — frantically sketched out a little of what they knew, and would leave feeling dissatisfied (or, alternatively, students would write something down and wonder if I’d give them credit for any of it, knowing full well that it wasn’t really what was being asked of them). And I just don’t have students doing that anymore.

When I am with a group of students (like a senior capstone seminar class) and we get to chatting about testing and things, I will ask them to compare the mastery approach to the summative approach, and they usually say that mastery is both harder, AND better. And this is consistent with the science. Mastery does indeed take work. The fun thing is, too, that when engagement with to-be-learned material is rich with varied opportunities to revisit via elaborative, applied, self-referential tactics, then it will “stick.”

That is, when learning centers on deep understanding, it gets in anyways. When the activities and assessments focus on “mastery”, memorization follows. I love that turn-about and I am sticking with this approach.