Why [what is a] “Psychsoundbite”?

Psychology has a public image problem and Psychsoundbites is here to help.

“Psychsoundbites” made its debut in the Fall of 2019, with one foot in the physical and one foot in the virtual world. In the physical world, that semester I rolled out a new assignment I’d created for my Intro Psych class that I called “the virtual soundbite” assignment (VSB), an assignment that in essence is a Psychology-meme-clean-up exercise. I promised my students that I would breathe virtual life into their best meme-corrections by posting them to the newly minted @Psychsoundbites Instagram account, and made good on that promise.

Since that first class I’ve continued with the VSB assignment and others that also involve the creation of catchy and concise and importantly accurate representation of psychological content in social media. My Instagram site has a modest following and a slow but steady stream of new content, some student-generated and some generated by me.

Why am I investing precious professional energy on something like this?

On the face of it, the meme-façade of Psychsoundbites may seem lightweight or even as a little frivolous pandering to my GenZ student body. But as I recently discussed the post Meme Matters [In Psychology], Psychological content on social media has a serious side, making the VSB and related assignments anything but frivolous. Turns out that Psychology, as a discipline, has a media misrepresentation problem. The broader purpose of PsychSoundbites is to address this serious issue, because real, personal costs can ensue from acting on mistaken beliefs or incorrect “knowledge” about Psychology.

Scot Lilienfeld – a dedicated champion for the cause of cleaning up Psychology’s long-standing multifaceted misrepresentation problems -- remarked in a 2012 publication …

… that we, Psychologists, are complicit in perpetuating our public image issues. That is, as a discipline, Lilienfeld noted, we have failed to police our own content and that we ignore our “problematic public face” at our own peril. While Dr. Lilienfeld (who sadly passed away in 2020) dedicated much of his prolific publishing energies towards remedying the problem of the public’s mistaken beliefs, much more work needs to be done in this area. My purpose with the Psychsoundbites endeavors is to make strides in helping to clean up Psychology’s virtual image, one “psychsoundbite” (or two or three) at a time.

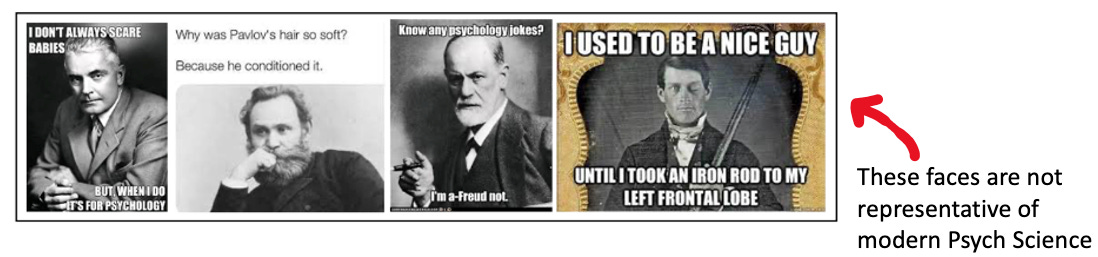

This is no small undertaking as it’s not just social media that gets so much of Psychology wrong. Psychology’s misrepresentation occurs in media broadly construed: social media, film, television, and print. And it has been for quite some time. Lilienfeld and others point to the Self-Help genre as one continuously problematic source (e.g., see Schamel, 2020 for a thoughtful discussion of this) of inaccurate representation of psychological phenomena, and to media personalities like Dr. Phil and Dr. Laura as well. Indeed, the extensive print media and talk-show coverage of the Moral Panic induced Memory Wars of the 1990s (e.g., Showalter, 1997) compounded the spread of misinformation and perpetuation of Victorian-era ideas in about emotion and memory that still resonate today, as well (i.e., as I say in my Cognitive Psych classes: The Memory Wars are Not Over; e.g., see Otgaar et al 2019 for detailed discussion of this). Add to this list popular television programs like Frasier and the fact that the ubiquitous faces of Psychology are still firmly rooted in the past –

For example, here’s a sample of what google images serves up to the query “Psychology Memes”, an issue I discuss at greater length on my WordPress site in an article titled Imagery: The Picturing Psychology Project --

and you start to see the problem: when all forms of media are flooded with outdated, incorrect, but provocative (and sometimes funny) “Psych-content,” and when folks consume that media repeatedly and uncritically, misinformation about Psychology sticks, making it increasingly harder to correct or update it. Just as there’s no free lunch, there’s no free scroll, either.

How widespread is this misinformation problem?

I check-in with my students at the start of each semester on their knowledge of “psych-facts”. What I consistently find is that even college students who have already studied some Psychology carry with them quite a bit of misinformation.

In one of my Cognitive Psychology classes, at the start of each semester I assess students’ endorsement of several common myths (e.g., misunderstandings, outdated knowledge) pertaining to relevant course content. Here’s a sample of what I find, based on data from the last three years.

Misunderstandings about memory and emotion. When it comes to relations between memory and emotion, I find for example that whereas 65% of students endorse Victorian-era beliefs that involuntary memory repression occurs, at the same time 63% also believe that we are wired to remember trauma for survival purposes and 34% believe that the more extreme the emotion, the more accurate the memory.

Misunderstandings about neuroscience. Twenty-four percent of students believe we only use 10% of our brains, and 75% believe that technology use is diminishing our brain power. Further, 21% of students believe that you are either right or left brained, and that females are “wired” for multi-tasking.

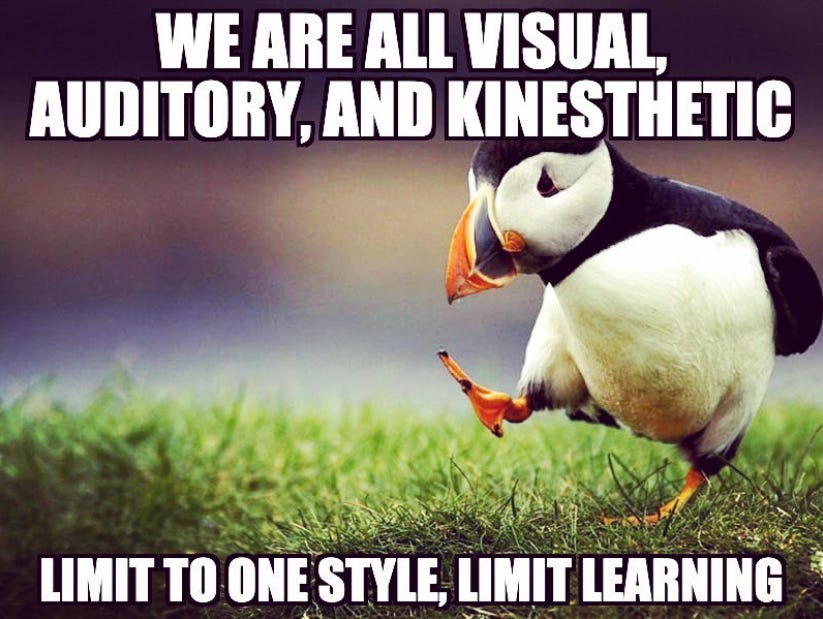

Misunderstandings about academic learning. When it comes to acquiring knowledge, 60% of my students enter classes believing that we all have a specific learning style, that is, that individuals are either visual, auditory, or kinesthetic learners and that they should get to experience a learning environment that supports their individual styles. And 42% of students believe that brain training exercises will enhance their achievement in higher ed.

Revisiting the causes of Psych-content misunderstandings

I’d like to reiterate that these are beliefs held by college students enrolled in a class with disciplinary pre-requisites. That is, these students have already studied the field either in high school (e.g., earning a score of 4 or 5 on the AP Psych exam affords students an Intro to Psychology waiver), college, or both before they’ve gotten to me. As such, it seems reasonable to assume that the folks who are not in college – or at least who aren’t studying Psychology in college – also endorse these myths to a similar degree, if not more so.

Many factors contribute to folks’ misunderstandings about psychological principles. The outdated and incorrect representation issue is only part of the story. The ways that we – everyday folks – think about human behavior plays a role too. Our brains are built to pattern-match, and this can lead us to draw incorrect conclusions when we are out in the wild just living life. Biases in reasoning like the hindsight bias (e.g., “I could have predicted that”) and confirmation bias (“Duh! Evidence for that is everywhere”) lead many to believe that Psychology is nothing more than common sense dressed up like a science. Another reasoning pattern that can be described as “simplicity seeking” (or cognitive miserliness) points to more a complex error of biological essentialism wherein one presumes a biological origin to all patterns of behavior and thus dismisses any other explanation (e.g., a psychological explanation of cause) as “incorrect.” Add to this the “illusion of understanding” problem, that is, the naive belief that understanding the causes of human behavior are easy, thus there’s no need for heavy-duty science work to determine what your grandparents already know from their “time on planet” and we have a perfect storm of misunderstandings of how our minds work being perpetuated by how our minds work.

For more on the notion that our minds trick us into holding overly simplistic views on our minds, see Adam Mastroianni’s article On the importance of staring directly into the sun; his overarching thesis differs from my point here, but the overlap with my thesis will take you on an interesting and enriching diversion.

One last compounding factor of note: Turns out that in the early days of our discipline, that is, back in the Victorian era, much theorizing was tantamount to introspection or self-reflection dressed up like science. Freud did not, as a general rule, use scientific rigor nor systematic data gathering to support his highly provocative ideas, rather he told wild tales of human nature illustrated with evocative examples.

For more on this point see Freud was a Fraud: A triumph of Pseudoscience.

Even though William James, a contemporary to Freud and author of the first Psychology textbook, remarked after Freud delivered a presentation at Harvard in 1909 that he (Freud) “made on me personally the impression of a man obsessed with fixed ideas”, when we skip ahead to the present-day Freud persists as the ubiquitous face of Psychology, whereas Psychology students only learn about William James in the history section of their Psychology classes.

Note: Thanks to Project Gutenberg, you can access a full text rendering of James’s 1918 text here.

All that is to say that in the early days, many (but certainly not all) initial ideas about “cause and effect” in Psychology were based on junk-science and speculation. And – importantly -- many of these ideas still circulate today in the media, whether as memes, as outdated content in high school Psychology curricula, as fodder for film and television sketches, or both. If that’s all folks know, because modern Psychological Science principles are not flooding the media spaces to overrule the old nonsense, then no wonder people “dismiss” Psychology with illusions of understanding and derision!

Does belief accuracy matter?

I mentioned earlier that holding mistaken beliefs about Psychological principles comes with costs, and that’s why I’ve taken up Lilienfeld’s call to contribute to the public clean-up efforts. While not all costs are equally damaging, it’s still worth it to address them. In the case of neuroscience, the belief that females are wired for multitasking feeds sexist stereotypes and that one simply needs addressing. Otherwise, the beliefs that technology changes the brain isn’t damning – heck, what students end up learning in my class is that EVERYTHING we do changes our brains. But the story is different with the others.

When it comes to mistaken beliefs about brain training and learning styles, one clear cost is that of opportunity – that is, students miss out on the opportunity to study in ways that will actually maximize their learning outcomes. Adherence to the learning styles mythos can also thwart motivation, in-class engagement, and enjoyment of learning. These beliefs can have financial costs too, especially in the case of brain training where one may pay money for apps or where public school districts spend money on learning styles assessment materials.

In the case of misunderstandings about the relationship between memory and emotion, belief in the possibility of repression can cause one to seek out dangerous therapeutic practices like Memory Recovery Therapy, practices that are no longer endorsed by the APA but still occur. Therapies rooted in the notion of repression and recovery by and large make patients worse, not better. Because the APA does not endorse such therapies insurance won’t cover it either, and so patients who experience distress and find themselves in a non-empirically based therapy situation are paying a significant amount of money for what amounts to malpractice.

How hard is it, to correct these beliefs? Turns out Psychsoundbites has much work to do.

For these reasons and more, I expend a significant amount of professional energy on updating folks’ beliefs and knowledge with modern Psychological Science content -- both in my classrooms and in social media.

Updating beliefs, especially beliefs like these that are personal (i.e., about ourselves), is difficult. Folks out there in the world living their lives don’t know that their Psychology knowledge is outdated, incorrect, or dangerous. They just have their knowledge and they carry on with it. And really, as discussed above many folks don’t think Psychology is a scientific endeavor anyways (Lilienfeld, 2012), or at the very least they assume that Psychology is pretty loosey-goosey and that their own intuition about how their own minds work is correct (e.g., Mastroianni, 2023).

When it comes to my classrooms, students expect to learn from me, so at least they are open to my messaging. However, even then it’s not easy. Many feel betrayed by their former – and often beloved -- teachers who steered them wrong by promoting unfounded, outdated and/or unsubstantiated claims about learning and memory (i.e., learning styles, unconscious repression). In a worst-case scenario, students compartmentalize what they learn …

“Prf. K. wants to hear this, whereas Prf. X. wants to hear that”

… thus knowledge updating doesn’t happen. In the best cases though updating does actually happen in my classes because I use our science to teach it, thus over the span of a semester I do successfully guide students to update their knowledge.

When it comes to interactions with the public in social media spaces, bringing attention to modern Psychological concepts is significantly more challenging, given that folks don’t realize they need a knowledge-update. While “informal teaching” in public virtual spaces is pretty different from the formal classroom gig, I can still look to our science for guidance. Schwarz, and colleagues (2016), for example, present well-researched and clear advice in their policy report titled Making the truth stick and the myths fade. Much more work in Cognitive and Learning Science besides speaks to the issue and I refer to that as I design my media posts.

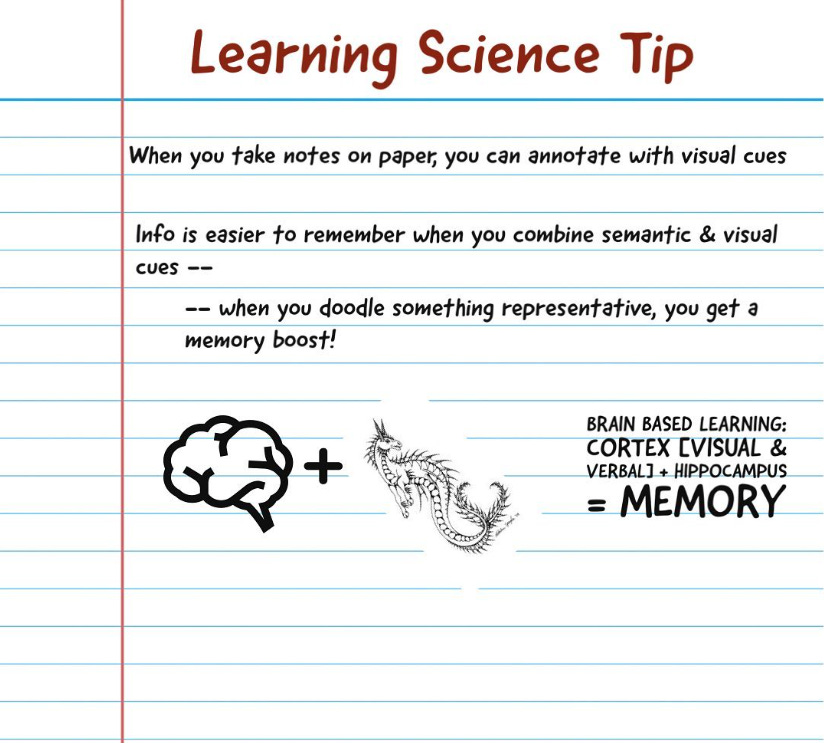

And that point takes us full circle: The design and intent of Psychsoundbites is to use Psychological Science knowledge about what makes content stick in our minds for good! As discussed in my Meme Matter’s article, for example, we know that the pairing of visual and verbal (semantic) content offers a memory boost. If you can layer in a narrative frame with an aptly selected meme template, then all the better.

Another point to consider: memories are strengthened by repeated exposure and access. By increasing visibility of catchy, modern, accurate Psychsoundbites, then that’s the content that will remain in the forefront of folks’ minds, supplanting the old outdated stuff. Exposure matters.

It will take more than a single authored site like mine to make good on the idea of flooding media with current, memorable content, but we have to start somewhere, right? Getting additional folks onboard with taking up this cause is another challenge that needs addressing. Many Professors will tell you that such work is not in their job description, and they aren’t wrong.

We – Psychology Professors - don’t learn how to communicate with the general public in graduate school. Nor do we learn how to make memorable memes. To the contrary, in graduate school we learn to communicate with a highly select few, using an esoteric vernacular and a dry technical writing style to boot. Media creation and mass communication skills are not in our Psych Grad curriculum.

Finally, our reward structure as faculty is based on publishing our work for a limited audience in scientific journals that have traditionally been tucked away behind paywalls. This is a difficult issue to broach – how do we incentivize the Professoriate to push back on an outdated system that disallows purposeful public scholarship? I don’t have a good answer for this. In my own professional life I made a decision to do it, despite the risk to how my work is reviewed by the personnel committee.

That said, I am working on developing my mass-communication skills to help get the word out. And that’s what Psychsoundbites is all about.

[How] Can you contribute to the cause?

By making it to this point you may be on board with the idea – the promise – of Psychsoundbites. If I am right, then you may also be wondering if you can help contribute to the cause. You surely can! Here are some ideas:

Subscribe, like, and share. My aims with Substack and my companion website (A work-in-progress as of summer 2024) are to continue to dole out modern explanations of human behavior in the areas that I believe most matter. Forthcoming content will mirror this one by pointing to a problem, offering explanation, and ending with advice for how to combat the issue. As of this writing, all of my content here on Substack is free, but subscriptions still matter so please subscribe! Subscriptions help me gauge my reach / impact and give me a concrete number that I can report back to the faculty review committee when I submit my work reports and resume updates. If you would like to support my work financially, rather than pay a subscription fee, please see the link below to my RedBubble site, and pick up a sticker, poster, button or t-shirt with one of my unique science designs, and bring some “psychsoundbite” content out into the real world.

Engage with the other arms of Psychsoundbites, too. Psychsoundbites extends into other media platforms, too and it’s reach is growing.

Instagram: Follow, like, and share what you see there!

Threads: Follow, like and share what you see there, and even better, share a comment too! Threads is a great place to chat about modern psych-science and build up a community.

BlueSky: This site operates much like Threads. As of this writing, I am trying out both Bluesky and Threads and will eventually settle with the one that seems to work the best and/or that engenders the best community.

Redbubble: Bring modern psych-science images into the physical world as a sticker, button, poster, or t-shirt. Adorn your water bottles, computers, walls, and office doors with modern psychology content, and support my work in updating Psychology’s public image.

Slow your scroll and think before you share. I don’t mean to be a complete kill-joy. Memes that poke fun at historical points of reference in the field are fun. But think before you promote these and consider how you might share modern content, instead. Or maybe for every single historical share, you share two modern points, as well?

Feeling creative? Make and share your own memes or visual content that feature modern psych-science concepts.

Got ideas but want to see someone else (like me, perhaps) create the content? I’m open to thoughtful suggestions. Leave a comment or send me a dm and let’s see what happens!