Representation Matters in Psychology

Or why modern concepts in Psych are not as well-known as they should be

I will address the title of this newsletter head-on, but I’d like to do a little stage setting first.

Setting the Stage: A little story about the power of imagery

When it gets out that I am a Cognitive Psychologist with a specialization in memory processes, like when I am on a plane and in a moment of distraction I forget myself and actually say what I do in response to the person seated next to me’s reasonable query, the conversation always goes something like this:

“Oh! You study memory? You should study me! I’d make a great case study. My memory is terrible… [insert personal anecdotes about forgetfulness here]”.

This predictable recitation is usually followed by a request:

“What can I do, to improve my memory? Can you help me?”

Turns out, I can help, and I’ll just do that right now, in case you too are thinking “can you help me, too?”!! I sure can. Here’s a solid pro-tip:

Imagery is powerful. The process of creating a mental image and linking it to conceptual knowledge is a tried-and-true memory boosting activity. Taking the outside world and bringing it in to your mind is a process some Psychologists call “mental representation.”

Our brains love images and nearly half of the cortex is involved in processing visual inputs. Our brains are wired to combine sensory-perceptual-motor inputs into meaningful “sets” that when activated will help us make smart predictions for wise action. Said another way: what makes our brains most happy is when sound, vision, movement, and meaning (semantics) are connected together.

Here’s an example of the power this process wields. What happens as you read each bullet point?

— Sound: Scuttle on the hardwood; bark, bark!

— Vision: small animal, four legs, fur, wagging tail

— Movement: wagging tail, moving paws, jumping and circling

— Meaning: My dog is happy to see me!

Each point above is made in words (symbols) that are literally [oh no, is that a pun??] just lines on a screen. Your brain translated the symbols into something else – a state of awareness in your mind, most likely a picture and that is, perhaps, one replete with sounds and smells and even emotions. If you were in a brain scanning device while reading these words, I could predict with accuracy where your brain would light up as you think about interacting with your happy-to-see-you-fur-baby: your visual cortex, your auditory cortex, your motor cortex, the olfactory bulb, and much more.

In the business, we say that mental experiences (memories) like these are contained in the brain via “distributed representations,” such that the flow of energy from neuron to neuron across multiple areas of the brain contains the various bits and pieces of your knowledge. When a particular pattern of neurons is activated, you experience “a memory.” As this happens you have a feeling of knowing or of re-experiencing. When a memory activates, neuron firing patterns serve to represent all the bits and pieces that together create the knowledge in your mind.

The more often sets of neurons fire together in the service of bringing to mind representations of your knowledge and experience, the more likely it is that the same sets of neurons will continue to fire together in future. Rather than “store memories” it’s more like the potential for memories that’s stored. Your experiences of remembering happen in the moment, as needed. In order to activate a memory, you need a match with cues: something from then (a sight, sound, smell, word, or emotion) needs to be cued in the now. A handy feature of this kind of storage and activation process – where parts of a memory are scattered all over the cortex – is that all it takes is one activation cue to get the whole network fired up.

— You hear a sound? Sound activates imagery, movement, and smell.

— See a picture of a dog? Images activate sound, movement, and smell.

— Smell “wet fur”? Smell activates images, sound, movement, and smell.

I hope you get the picture. In this system, the PICTURE is a powerful piece of the memory process and images are powerful memory cues. When you need to learn “content” whether that’s a list of vocabulary words or competing theories for a single idea, or just a shopping list, pairing meaningful images to the words will super-charge your memory process.

This principle has a long-standing research history behind it, from an accumulation of work spanning the 20th and 21st centuries. In a field where known-facts often change as research programs progress, such reliability is a rare gem. You really can’t go wrong with blending semantics and imagery. You can sketch [doodle] the images, embellish your notes with digital images, or even create clever memes to capture key points!

With this mini-lesson in mental representation now in your back-pocket, let’s change gears and dig-in to the heart of the matter: What is Psychology’s Representation Problem? Why does it matter?

The short of it: The more you experience a particular input, the more likely it is that that input will seemingly instantaneously activate connected content, giving you a solid feeling of knowing.

More on Representation: Using one thing to stand for something else

Lately we’ve been hearing about serious representation issues in the news media related to generative AI (e.g., Humans are Biased. Generative AI is Even Worse). It comes up a lot in the context of government too, for example whether the US congress represents the population (It doesn’t, according to this 2021 Pew Research Center report). It’s also frequently discussed in the media in terms of who we see pictured in movies and television, for example: Why Movies like Black Panther Matter.

Generally speaking, a representation is something (e.g., a picture) that stands for something else (an abstract concept). In the case of memories, the neural activation pattern stands for the original experience. In like manner:

— A “headshot” image created by Generative AI is a summation of all the data used to train the model that links to the query or prompt

— In the case of government, the voice of each “representative” supposedly echoes the will of their constituents

— In the case of film and television, the actors portray scenarios of what the world is, or could be, like

All of these portrayals (AI generated images, the “face” of US government, and “the faces” in entertainment media) feed mental models of our socio-cultural-political worlds. Images are “Psychologically sticky,” that is memorable. Images connect with conceptual knowledge in our minds, feeding a feeling of knowing.

When images and the linked conceptual knowledge do not adequately represent reality, then problems may arise. The compounding effect of repeatedly experiencing non-representative imagery creates expectations that are different from reality, and among other things, feeds implicit bias and the perpetuation of stereotypes. It’s really a simple recipe – biased beliefs are formed by a barrage of biased inputs.

Representation Matters, in Psychology

Representation matters in Psychology in the same ways it matters for government and generative AI.

While working on this newsletter, I came across an article in Perspectives in Psychological Science titled (Why) Is Misinformation a Problem? A point Adams and colleagues (2023) make is that to everyday people who engage in conversations, consume information online and just go about their lives, their sense of reality is not an objective state that they’ve discovered and plunked into their heads. Rather, what one deems “reality” is an intersubjectively derived representation of experiences – importantly interactive experiences with others and with media content. Said another way, we create our own sense of what’s real by interacting with what and who is around us.

Philosophers and psychologists both have discussed this issue in many guises and for many years. Adams and colleagues raise the issue again in light of the impact that social media is having on this process. Key take away from their discussion is while there is an objective reality that *could* be discovered, we rarely curate our experiences enough to build well-rounded and objective conceptual knowledge. That takes discipline and work we usually assign to “school” not to life. Rather, we experience what we experience, and go from there feeling like we know what the world is about.

What is it that’s misrepresented?

We are now at the heart of the matter. Media representations of psychology content do not represent the field, rather media portrays an outdated and biased view. What does this view “look like”? Here’s an example.

I made this meme a few years ago after reviewing my Intro to Psych students’ early semester submissions of their subjective concept maps depicting what they know already about Psychology [I love this activity for many reasons!]. One student created a “node” on their map and labeled it “Old White Guys.”

Psychology has a representation problem because that is what the face of Psych often looks like in the media – Freud, Pavlov, Skinner, Watson, Maslow.

In the real world nearly 70% of the Psychology workforce is comprised of Females ages 36 - 55.

This mismatch matters. Representation via the media tokens used to stand for Psychology as a scientific discipline (e.g., images, memes, definitional soundbites) matter because if the tokens are misleading or far from an objective truth, then folks’ understanding of Psychology is, well, mislead too.

The faces that portray the field in the media create mental models that beliefs and behaviors follow from. When the discoverable faces that represent Psychology are primarily Caucasian and male, an implication comes along with the pictures: The pictures are taken as representative of who works in the field, signaling either an in-group invitation (e.g., “I belong”) or an out-group sense of hesitancy (“Do I belong?”).

And when the content of Psychology associated with those faces follows, then one has a feeling of knowing about the field, but what you think you know isn’t actually what the field is really about, anymore. When the signal “out there” in the media is that Psychology remains rooted in Freudian mythos, then an opportunity cost (e.g., learning and benefiting from empirically sound psychological content and reasoned advice) follows wherein folks who might actually benefit and enjoy modern Psychology dismiss and ignore it, thinking it’s just weird, or common sense, or non-scientific. What a shame this is.

The discipline’s representation problem with the media is a problem of message control. Modern Psych Science has much to offer everyday folks, but who would know, when the media is so firmly rooted in the past? I discuss the issue of misunderstanding in the post Why [what is a] Psychsoundbite too – I encourage you to take a look there for more concrete examples of common misunderstandings. Some misconceptions reflect over-circulated outdated content, and it bears repeating that we’ve come a long way from the Victorian era. Others come from over-circulated content that is just plain false.

On that point about updating, let’s circle back to the stage-setting scenario and the power of images. It turns out that the advice I shared earlier about the power of linking imagery and concepts together isn’t widely known. And some folks who have encountered the advice dismiss it, because – in their own words – “they aren’t visual learners so it won’t work for them.”

Why isn’t the Pro-Tip [imagery boosts memory] more widely known?

Turns out that that self-defeating dismissal of solid memory advice reflects a steadfast and common belief in the pseudoscientific notion of Learning Styles. When I discuss the fact that we are all visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learners, along with other principles that come from Learning Science with my undergraduate students, many students have “Why I am just learning this now?!?” moments.

Why indeed are they just learning it now? It comes back to the mis-representation issue. When you search the media for information on how to boost learning, you will find more “hits” for compelling, easy to imagine anecdotes in support of Learning Styles, than you will find compelling content that reflects modern Learning Science.

There is no valid scientific evidence in support of “learning styles” and in fact, the premise is at odds with what we know to be true about the neuroscience of memory processes. While individual differences in cognitive prowess and control do exist, the Learning Styles framework is not one of them. But the prevalence of compelling visual, or easily visualizable media promoting the perspective continues to feed beliefs in its usefulness as a teaching tool.

Even though you didn’t know, you did, actually know?

Once you take a moment to think about this, I expect you are starting to realize that you actually knew this already. Our digital world is full of imagery and images stick! We love our memes, Tik-Toks, Reels, and infographics. We don’t want to read plain text anymore – we want pictures to help us understand. We want our …

We seek out images, share images, laugh and cry at images. Over our lifetimes many of us spend thousands of dollars on glasses and contact lenses to correct our imperfect vision. But -- we also underutilize this knowledge, even when we are in the know!

Proof that Psychology needs an image update.

Back to the representation issue in Psych — by “we” in the last sentence above I mean Psychology. Psychologist Scot Lilienfeld spent a significant portion of his career working towards correcting our image problem, and in 2012 he stated that as a discipline we have failed to adequately manage our reputation and disciplinary knowledge with the general public. This remains true today. Despite his and others’ efforts, the full scope and modern scientific knowledge is still not well represented across the media landscape. Especially the visual media landscape.

A google images search for “Psychology Memes” generates an array of meme-template faces interspersed with the same old array of 19th & 20th century figures: Watson, Pavlov, Freud, and Phineas Gage. I am a huge fan of a good Psychology pun, meme, or joke, but this isn’t a good look for us when that is all there is. In the media, the face of Psychology is firmly rooted in the past.

I know I can find more when I work on refining my search criteria, but folks, it is a hard slog.

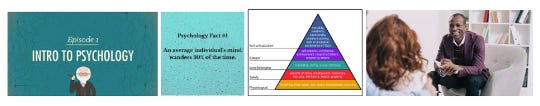

When I put a different spin on the query and instead type “Show me Psychology,” what do I find? An array that is a bit more colorful, but the results are still not great otherwise. Here’s a snapshot of what that search query yields: Cartoon renditions of Freud, “Psychology facts” that are, in fact, incorrect, disproven theories and a lot of stock photos of faux counseling sessions. As with the meme-search, this is not a good look for us, either!

The story told by the image array here is an outdated story that mis-represents modern psychological science.

What’s wrong with the story told?

— Freud’s ideas are Victorian – that is, Old! Outdated! More often than not, incorrect! He is not the face of modern Psychological Science and he should not get so much digital face-time.

— That Psychology fact is incorrect. The actual number is 50% -- our minds wander a lot!

— Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs was only ever a speculative hypothesis and was never based on empirically derived data. Modern research on motivation tells a very different story.

— Only just over 50% of individuals who work in the field of Psychology are clinicians, but you would never know this from the stock-images and media portrayals.

Seeking out existing content is one thing, but what about generating new content? Generative AI is becoming increasingly accessible and I’ve been spending some time with it myself. I put my query into DALL-E3 too (“Show me psychology”) and the yield is visual nonsense.

Does Canva’s “magic studio” fair any better? To test this out, I decided to give the program a leg up by giving it some statistics from the American Psychological Association’s dashboard featuring current demographics of the Psychology Workforce in the US (see dashboard here).

As of 2021, nearly 70% of the Professional Psychology workforce is comprised of females aged 36 – 55. By the numbers the workforce is not as diverse as the population, such that about 80% of the Psychology workforce is Caucasian.

Here’s the prompt I used: “Create a group of professional psychologists in a meeting: 69% are female and 80% are Caucasian” …

…And here’s what Canva created for me:

While not nonsense (so better than DALL-E3), these images still completely miss the mark. As with the Bloomberg study about human and AI bias linked earlier in this newsletter, even with a clear prompt, generative AI output is only as good as the data it has to draw upon. Adobe Firefly didn’t get it right either …

… and the more powerful combo of ChatGPT-4 + Dall-E wouldn’t make an image, and instead created this:

With a little further refinement to my prompting, I got this —

Which is decidedly not what I asked for.

How about just plain old ChatGPT? I found that the free version can generate a decent verbal recitation of what Psychology is all about (see it’s response here: What does Psychology Look like?). So while OpenAI’s conceptual knowledge base does get some things right about modern Psychology (in text), when it comes to visualization, the AIs struggle because the data they have to work with isn’t representative.

Why is all this problematic?

Visual representation matters for the field. As with STEM, when individuals don’t see themselves pictured in the field, they are less likely to pursue that field. This is indeed one contributing factor (of many) to the lack of diversity in the Professional Psychology workforce. Psychologists Martin Conway & Catherine Loveday (2015) explained this connection between mental representation, identity, and future goal setting with what they called the “Remembering – Imagining System (RIS).” The RIS is a mental framework that guides future decisions by using what you remember from past experience and projecting that content into a “future self” scenario. If you can imagine it, you can become it, sort of thing. Bringing this back to the present issue: when the content that feeds the RIS is biased, the way you then imagine your future self is also biased.

Following, the “old white guy” imagery that simultaneously evokes outdated Psychological content creates other problems too. For one, it creates a missed opportunity for the field! Psychology’s purpose is to use the principles and process of science to learn about the causes and consequences of human behavior so that we can then find ways to improve conditions for individuals, for families, and even society. Our representation problem is getting in the way of our mission.

How do we fix this problem? One approach is to start flooding the digital media ecosystem with new, compelling, and modern visual content.

— Stop circulating the old stuff (I hesitated to even include it here, but needed it to, make my point)

— Make new memes with modern topics and breath virtual life into them by circulating broadly

— Feature diverse faces that represent the actual workforce

— Create other kinds of images that feature modern principles in Psych Sci.

I am working on this myself.

I make graphics and memes for my classes, I invite my students to do the same (and in some cases we fix incorrect memes and recirculate the fixes), and I am making stickers and posters too. Some are featured here in my Substack newsletters, and you can find even more on my Instagram and Redbubble sites.

If you like what you see in IG, “like” and “share” it. If you want to decorate your office walls or doors, check out Redbubble and buy a poster or two (this one pictured above looks great on my office irl!). If stickers are more your speed, then grab some of them instead and adorn your water-bottle or computer or both!

My representation upgrade mission is actually pretty fun, and I’d love to see you join me. Representation really matters, and with a little vision and attention paid to making algorithms work for us instead of against us, we can make good strides in making good on the overall raison d'etre of this varied, intriguing, and useful field.

—

[End Note: An earlier version of this newsletter can be found on my other blog, CognitionEducation, a blog project I am winding down, as I wind up here, on Substack.]